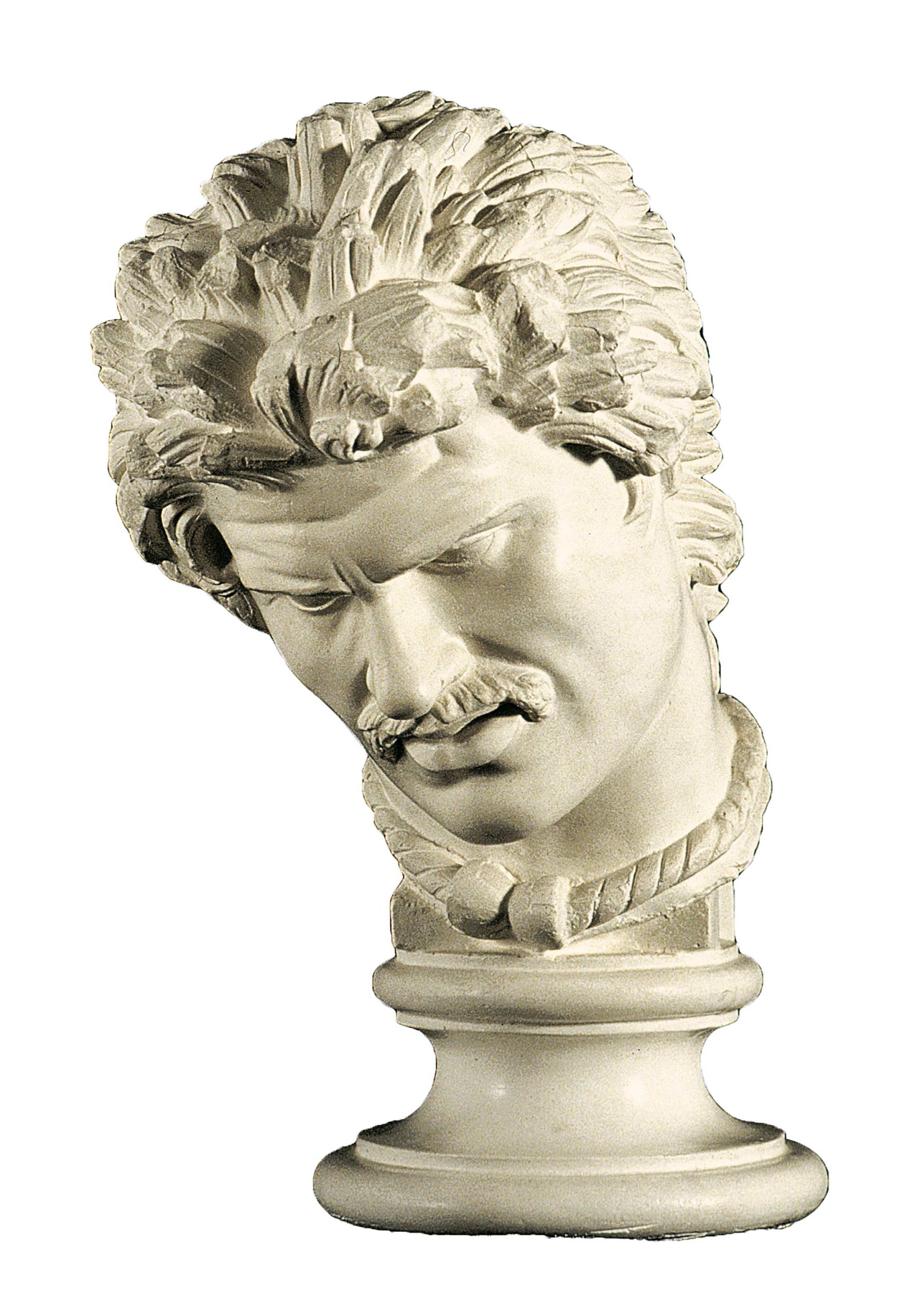

Work: Head of the Dying Gaul, or Galatian

Copy of sculpture

Copy

- Dimensions

- 37 cm high, 36 cm wide, 26 cm deep (detail)

- Technique

- cast from the original

- Material

- alabaster plaster

- Space

- Facial expressions

Original

- Date

- I century BC

- Period

- Greek

- Dimensions

- 75 cm high, 185 cm wide

- Material

- marble

- Location

- Capitoline Museums, RomeSi apre in una nuova finestra

Photo: Maurizio Bolognini. Museo Tattile Statale Omero Archive.

Description

“They say that is how heroes die. They call it the beautiful death. I don’t know if I am dying as a hero. What I know is that I am dying free”.

The Capitoline Museums, where the original Dying Galatian is conserved, attributes these last words to the character depicted. The head is the second work in the Museo Omero’s Gallery of Human Facial Expressions.

The original sculpture represents a dying warrior and is a Roman marble copy of one of the bronze statues that made up the huge sculptural group dedicated to Athena Polias, situated on the Acropolis of Pergamon, in memory of the victory of King Attalus I (241 . 197 BCE) over the Galatians.

The complete original sculpture portrays the warrior on the point of death, with his body collapsing onto his shield. In true Hellenistic style, the Galatian’s face is modelled with extreme attention to the naturalistic details: the cheekbones are pronounced, the teeth can be glimpsed between the slightly opened fleshy lips; his moustache is bushy, while his hair is thick and divided into tufts, because of the animal fat that they used. He wears a torque, the typical Celtic neck ring that indicated the high social rank of the wearer and supposedly had a religious or magical meaning. The term torque derives from its twisted shape. His furrowed brow and his slightly bulging temples convey the warrior’s resistance to pain, a proud attitude that shows no sign of surrender. The introduction of the representation of pathos in the visual arts is also a typical element of the Hellenistic period.

The valour and the virtue of those warriors were understood and acknowledged even by the victors: the author of the work set in bronze the bravery and determination of the enemy, capturing the spirit of the one who dies with honour.

The marble copy was commissioned by Julius Caesar for his Horti: he probably chose this subject for propaganda reasons, in a parallelism with his military campaigns, seeing in this sculpture a kind of symbol of the worth of those who had defeated such courageous enemies.